"The Enthymeme is a (rhetorical) syllogism". Aristotle, Reth. II, 22

"Rhetoric may be defined as the faculty of discovering the possible means of persuasion." Aristotle, Reth. I.2.1

Labels

Philosophy

(28)

Logic

(22)

Probability

(21)

Argumentation

(20)

Ramus

(20)

Literature

(15)

Assumptions

(14)

Handouts

(11)

Mathematics

(11)

Metaphors

(11)

Quotes

(11)

Matlab

(10)

Tropes

(10)

Method

(9)

Quintilian

(9)

Induction

(8)

Modeling

(6)

Book Reviews

(5)

Collingwood

(5)

Physics

(5)

Problem Structuring

(5)

Analogies

(4)

Historiography

(4)

System

(4)

Aphorisms

(3)

Classical

(3)

Evidence

(3)

Fallacies

(3)

People

(3)

Religion

(3)

Transitions

(3)

Decision Making

(2)

Dynamic Programming

(2)

GIS

(2)

Linear Programming

(2)

Poetry

(2)

Sayings

(2)

Toulmin

(2)

Writing

(2)

economics

(2)

Art

(1)

Bach

(1)

Policy

(1)

Regression

(1)

Risk

(1)

Showing posts with label Logic. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Logic. Show all posts

The past is a foreign country

The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” ― L.P. Hartley,

Reason teacheth and experience evidenceth

Reason teacheth and experience evidenceth in Miller, P. (1939) New England Mind, p. 7

System of Knowledge and Explanation

Introduction to R. Moshe Luzzatto (Ramchal) Derech HaShem."Organized knowledge of a subject and the interrelationship of its various parts, is superior to disorganized knowledge – just as a beautiful garden arranged with beds of flowers, paths and rows of plants is superior to a chaotically overgrown forest...A person should always endeavour to grasp general principles...When a person understands one principle he automatically understands a great number of details."

Wesley Salmon (Four Decades of Scientific Explanation, 1990) argues a description of what "explanation" is:

The challenge is when we're aware that we don't know adequately or completely the regular patterns, or mechanisms that produce the events, and we know that we never will know them completely.[explanations] show how empirical phenomena fits into a causal nexus (paraphrase p.121)... the explanation of events consists in fitting them into the patterns that exist in the objective world. When we seek an explanation, it is because we have not discerned some feature of the regular patterns; we explain by providing information about these patterns that reveals how the explanandum-events fit in.... explanation reveal the mechanisms, causal or other, that produce the [events] we are trying to explain. (p 121).

Historical Explanation

Good resources are offered in:

- Bennet and George (1997) Process Tracing in Case Study Research. MacArthur Foundation Workshop on Case Study Methods. HERE.

- Clayton Roberts (1996) The Logic of Historical Explanation. Pennsylvania State UP.

The problem of "influences" in the history of ideas

The problem of "influences" in the history of ideas is another perpetual problem. "Action at a distance" seems to be admissible in the field of intellectual influences

The problem of "influences" in the history of ideas is another perpetual problem. "Action at a distance" seems to be admissible in the field of intellectual influencesCollingwood's pronouncement:

"...these methods of description are characteristic of that frivolous and superficial type of history which speaks of ‘influences’ and 'borrowings’ and so forth, and when it says that A is influenced by B or that A borrows from B never asks itself what there was in A that laid it open to B’s influence, or what there was in A which made it capable of borrowing from B. An historian of thought who is not content with these cheap and easy formulae will not see Hegel as filling up the chinks in eighteenth-century thought with putty taken from Plato and Aristotle." Idea of Nature, 128

Claudio Guillen

"... to ascertain an influence is to make a value judgment, not to measure a fact. The critic is obliged to evaluate the function or the scope of the effect of A in the making of B, for he is not listing the total amount of these effects, which are legion, but ordering them. Thus "influence" and "significant influence" are practically synonymous."Very interesting insights from Hyrkkänen (2009):

- according to the influence model, to explain some element of the thought of a writer A is to maintain that A has been influenced by an earlier writer B, i.e. A has adopted an element into his thinking from the works of B, or from discussions with B, or, indirectly, via C, or in some other way.

- According to Hermerén, the influence model is misused if research is ‘totally dominated by the search for influences’ – if, in other words, ‘the billiard ball model of artistic creation’ is followed.

- Adopting an influence entails reflecting on alternatives, which is a process of weighing more or less consciously the available influences.

- If we perceive an adopted influence as an answer to a question, or more generally, as a solution to a problem, it becomes understandable why human beings are receptive only to some but not to all possible influences.

- The cases of Vico and Hegel illustrate how people set apart by time can be reunited by similar problems they happen to share. Moreover, for the very reason that human beings may share similar problems, they may arrive at similar solutions.

- ...it would be more promising to try to explicate and understand the reasons for the similarity of problems.

- In the case of independent invention, the interpreter has to consider or imagine the alternative solutions to the problem the inventor had in mind. In the case of an influence being adopted, the task of interpretation is to understand why the agent happened to select a certain influence from the available alternatives. In both cases, the central task of the interpretation is to answer the question of why an idea has, more or less consciously, been adopted.

- Intellectual debts

- Source of stimulus for his own philosophizing

- parallels and similarities of doctrine

- ideas traceable to x

- "Collingwood ask us to focus not on what was borrowed, but on what led the borrower to select what he did. Intellectual borrowing tells us something about the borrower only if we go on from there to examine how it fits into the body of his thought. A corollary of this view, which Collingwood does not spell out but which he implies throughout his analyses of other men's thought, is that to borrow is to interpret... It was the multiplicity of his interests and his command of many fields of learning which made Collingwood "capable of borrowing" from Croce, Gentile, and Vico. It was his almost unique intellectual versatility which "laid [Collingwood] open to their influence." p. 87

- "If the source of specific ideas in Collingwood is obscure, the inspiration behind his life-work is clear. He is the fully-educated man, full according to the ideal of John Ruskin... One might say of Collingwood, as of Ruskin, that he is himself the greatest influence on his own thought." p. 89-90

- Hyrkkänen's All History is, More or Less, Intellectual History: R. G. Collingwood’s Contribution to the Theory and Methodology of Intellectual History.

- Claudio Guillen's The Aesthetics of Literary Influence, p. 38-39

Flesch–Kincaid Readability Score

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flesch%E2%80%93Kincaid_readability_tests

https://www.timetabler.com/reading/

Pons Asinorum in Logic

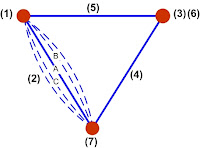

| Pons Asinorum. Kneale & Kneale 186 |

|

| A nicer pons asinorum from the 17th century. Source unknown |

Chrysippus and his indemonstrables modes of reasoning

From the Jeremy Kirby's entry on Chrysippus in the IEP.

From the Jeremy Kirby's entry on Chrysippus in the IEP."...Aristotelian arguments above made use of classes. The ... relata herein are propositions [not classes]—Stoics called these ‘sayables’—rather than classes. In Aristotelian logic, the key connectives are ‘all’, ‘some’, ‘is’, and ‘is not’. In Chrysippus’ logic, the key connectives are ‘if’, ‘or’, ‘and’, ‘not’. "

The consequentia mirabilis

If a proposition follows from its own negation, then it's true.

Descartes:

Angelelli, I. () Here

Mirabell, I. () Here

Kneale, W. () Here

(¬A→A)→A

Some instances in which this deductive method is used are:Descartes:

- Cogito: I think

- <> all that thinks exist

- ergo sum: therefore I exist.

- Suppose that all my knowledge is false

- but at least I know that I know something, although it's wrong

- Therefore in knowing that I know something, I don't deceive myself

Angelelli, I. () Here

Mirabell, I. () Here

Kneale, W. () Here

Collingwood + Rex Martin on what is Historical Explanation

It may seem that the best summary of Collingwood's thinking was elicited by Dray:

The statistical criteria for proving the relevance are taken from Wesley Salmon:

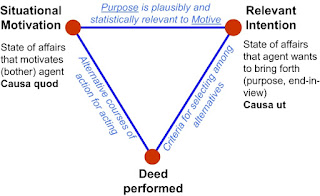

"...for in so far as we say an action is purposive at all, no matter at what level of conscious deliberation, there is a calculation which could be constructed for it. .. And it is by eliciting some such calculation that we explain the action." Laws and Explanation in History 123and C. Devanny (Dray actually),

"...what we very often want is a reconstruction of the agent's calculation of means to be adopted toward his chosen end in the light of the circumstances in which he found himself." (Laws and Explanation in History, 116-122)Next figure is adapted from Rex Martin's Historical Explanation p. 69

Rex Martin expressed the meaning of each node and side of the triangle in a schema of seven propositions:

- The agent perceived himself to be in a certain situation and was disposed to act toward it in some definite way (e.g., as Caesar was disposed to curb the hostile incursions of the Britons).

- There were a number of alternative courses of action (designated as A-e.g., invading-B, C, and so on) open to the agent who had the situational motivation described in (1).

- The agent did want to achieve or accomplish such-and-so end (e.g., conquest), which he believed would satisfy his situational motivation.

- He believed that doing A was, in the circumstances already described, a means to accomplishing his stated purpose or a part of achieving it.

- There was no action other than A believed or seen by the agent to be a means to his goal which he preferred or even regarded as about equal.

- The agent had no other purpose which overrode that of accomplishing such-and-so.

- And we might add, although Collingwood gave little attention to it, that the agent knew how to do A, was physically able to do it, would be able to do it in the situation as given, had the opportunity, etc

I interpreted it graphically as (though not sure on 5 and 6):

The statistical criteria for proving the relevance are taken from Wesley Salmon:

- Statistical relevance: (called simple relevance by Martin)

- Screening-off: (Outweighing or overruling)

- Homogeneity of the reference class (intrinsic relevance)

Futuritionis

Futuritionis is a latin term which was related to the concept of probability and also of potentiality. Was it related to the future prediction of something?

The full spectrum of terms is: pastness (praeteritionis), presentness (praesentalitatis), and futurity (futuritionis).

Certitudo rei cujusvis spectatur vel objective & in se; nec aliud significat, quam ipsam veritatem existentiae aut futuritionis illius rei: vel subjective & in ordine ad nos; & consistit in mensura cognitionis nostræ circa hanc veritatem. . . . Probabilitas enim est gradus certitudinis, & ab hac differt ut pars a toto.

From the DMLBS (http://logeion.uchicago.edu) qua contingenter

Jacob Bernoulli. The Art of Conjecturing, together with Letter to a Friend on Sets in Court Tennis. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2006. Translation of [22] and commentary by Edith Sylla. 9, 99, 100

The full spectrum of terms is: pastness (praeteritionis), presentness (praesentalitatis), and futurity (futuritionis).

1. Mathematical Meaning

Here's some texts (J. Bernoulli Ars Conjectandi):Certitudo rei cujusvis spectatur vel objective & in se; nec aliud significat, quam ipsam veritatem existentiae aut futuritionis illius rei: vel subjective & in ordine ad nos; & consistit in mensura cognitionis nostræ circa hanc veritatem. . . . Probabilitas enim est gradus certitudinis, & ab hac differt ut pars a toto.

Translation Sylla p. 315Translation mine:

The certainty of anything is considered either objectively and in itself or subjectively and in relation to us. Objectively, certainty means nothing else than the truth of the present or future existence of the thing. Subjectively, certainty is the measure of our knowledge concerning this truth. . . . Probability, indeed, is degree of certainty, and differs from the latter as a part from the whole.

The certitude of things obtains either as objective, i.e. essentially, meaning nothing but the reality of the thing's existence or futurity, or subjective, i.e. arranged to us, consisting in the extent of our knowledge about that reality.

Everything under the Sun that is or has been, past, present, or future, in itself and objectively, always has total certitude. It is apparent what is present and past, for in their very existing or having existed, cannot be otherwise. Nor should be argued of future things.

From the DMLBS (http://logeion.uchicago.edu) qua contingenter

- hic quidem intellectus propheticus est cujus speculum est semper eterna intueri et ab ipso perfici, in quo etsi omnia presentialiter sciebantur, tamen ea que hic preterita sunt aut futura ibi sine preteritione aut futuritione in preteritione et futuritione sua dinoscuntur Ps.-Gros. Gram. 15;

- causa vero in actu est quod presencialiter causat rem, causa in potentia que de futuro potest causare, unde actus hic est presencialitas, et potencia sonat in futuritionem Bacon II 129;

- ‘quando’ respicit partes temporis signatas, sc. preteritionem et futuritionem Ib. VIII 264; ex dictis patet quomodo solvi debeat ad argumenta ad aliam partem: bene enim probant quod futuracio rei non est causa sciencie Dei; sed ex hoc non sequitur quin concurrat ad hoc quod in sciencia Dei sit relacio racionis per quam habet racionem presciencie Middleton Sent. I 338; c1301 an futurum contingens possit certitudinaliter cognosci alia cognicione quam beatifica. ‥ primo cognicione naturali, quia certitudinem illius cognicionis non impedit futuritio nec contingencia Quaest. Ox. 299;

- si voluntas divina esset causa futuritionis omnium futurorum, esset causa veritatis omnium proposicionum verarum, eciam contingencium de futuro Bradw. CD 212C;

- ad secundum dicitur quod assumptum est impossibile. cum non sit possibile Deum preordinasse produccionem prime creature, nisi per instans primum cujus est, futuritio non fuit, nec potencia ante actum ‥; quamvis forte futuritio mundi sicud et cujuscumque alterius rei sit eterna a parte ante, nec alia est futuritio, cum res fuerit et alia antequam fuerit, et sic futuritio prime creature est eterna Wycl. Log. III 226;

- sic aliqua sunt et necessario existunt, ut Trinitas increata, aliqua sunt et necessario non existunt ut pretericiones, futuritiones, possibilitates Id. Ver. II 128;

- 1412 sicut Deus necessitat futuracionem parcium, sic necessitat ad omnes eventus , qui in illis partibus sunt futuri Conc. III 349;

- futuritio ergo rei est verum objectum presciencie ut presciencia est Netter DAF I 81a.

2. Theological Meaning

For one thing, the locution Futurition is almost always found in theological treatises. One instance of such discussion is afforded by a lengthy philosophical consideration by Richard Baxter (1615-1691) in An ANSWER TO Mr. Polehill's Exceptions about Futurition.

In Reformed circles: Leidecker, Burman,

Another example is the Franciscan Bonaventura: ratione futuritionis. (Sent., Bk. I, d. 41, a. 2, q. 1, 4 arg. ad opp.).

Or Aquinas ratio futuritionis futurorum.

Or Tomasz Młodzianowski (1666)

Si autem nulla futura fuissent futura, processisset verbum ex cognitione non futurae futuritionis futurorum.

Or Aquinas ratio futuritionis futurorum.

Or Tomasz Młodzianowski (1666)

Si autem nulla futura fuissent futura, processisset verbum ex cognitione non futurae futuritionis futurorum.

3. Philosophical Meaning

Kant following Leibniz said:

The events which occur in the world have been determined with such certainty, that divine foreknowledge, which is incapable of being mistaken, apprehends both their futurition (futuritio) and the impossibility of their opposite. New Elucidation 1:400.

References:

Jacob Bernoulli. The Art of Conjecturing, together with Letter to a Friend on Sets in Court Tennis. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 2006. Translation of [22] and commentary by Edith Sylla. 9, 99, 100

Presumption and Probability in Talmud

Hazakah indicates presumption and sometimes coincides with rabbah, or rubba, or rov which is the rule of the majority, or a type of frequentist probability.

There's an 11 volume work on hazakah by R. Jacob L. Kroch.

References:

Kroch, Jacob Leib ben Shemaiah. Encyclopaedia Judaica. . Encyclopedia.com. (February 19, 2017).

J.L. Kroch, Hazakah Rabbah, 1 (1927), introduction by P.J. Kohn; J.L. Kroch, Halakhah Rabbah, 2 (1966), introduction by A. Krauss.

There's an 11 volume work on hazakah by R. Jacob L. Kroch.

References:

Kroch, Jacob Leib ben Shemaiah. Encyclopaedia Judaica. . Encyclopedia.com. (February 19, 2017).

J.L. Kroch, Hazakah Rabbah, 1 (1927), introduction by P.J. Kohn; J.L. Kroch, Halakhah Rabbah, 2 (1966), introduction by A. Krauss.

Argument moves in Babylonian Talmud

The Talmud provides interesting techniques of logical analysis and debate. For all its logical value, Talmudists devised and applied conceptual instruments to unravel tacit implications or ramifications in arguments. The arguments put forward are subjected to these conceptual instruments in order to test their cogency or validity to the extreme. These instruments frequently are casuistic hypothetical situations, applications of Mishna, Baraitot, etc. To the superficial eye, Talmudic arguments seem artificial and not a few times bordering on the absurd. However, these conceptual instruments have a surgical function which they perform well and are very helpful for the patient student.

R. L. Jacobs (The Talmudic Argument, CUP, 13f) asserts that the following argumentative moves are found in Talmud:

- Arguments based on pure reason

- Argument from authority

- Argument from comparison

- Argument by differentiation

- on the contrary argument

- acceptance of an argument in part

- Argument based on an opponent's position

- Argument exposing the flaws in an opponent's argument

- Arguments based on the facts or interpretation of facts

- Argument based on geographical or historical conditions

- Argument based on the analysis of states of mind

- Other types of arguments

- Readmission of an argument that has been previously rejected

- Argument against a statement of the obvious

- Arguments from Texts

- Argument to resolve a contradiction between two sources

- Argument by textual emendation (Mishnah)

- Argument from the principle of literary economy

- Versions of the same argument

- argument presented by different teachers

- consequences of different arguments

- limited application of an argument

Majority, Multitude, and Probability in Biblical and Talmudic writers

R. Louis Jacobs observes that:

Thus probability in Hebrew is rab (רָב, abundance). It seems an interesting vindication of the frequentist version of probability! But specifically, it reinforces the intuitive idea that probability are statements about aggregates.

Interestingly enough, there is the the Justinian Digest a rule of thumb to overcome evidential deadlocks enunciated by Paulus that hinges on the concept of the majority (plerumque):

Reference

Jacobs, L. (1984) The Talmudic Argument. Cambridge UP, p. 50f.

Thus probability in Hebrew is rab (רָב, abundance). It seems an interesting vindication of the frequentist version of probability! But specifically, it reinforces the intuitive idea that probability are statements about aggregates.

Interestingly enough, there is the the Justinian Digest a rule of thumb to overcome evidential deadlocks enunciated by Paulus that hinges on the concept of the majority (plerumque):

In obscuris, inspici solere quod, verisimilius est, aut quod plerumque fieri solet. Corpus Iuris Civilis, Justinian Digest 50.17.114.

(when there is obscurity, we usually regard that what has appearance of truth or what is mostly done)

Reference

Jacobs, L. (1984) The Talmudic Argument. Cambridge UP, p. 50f.

Talmudic reasoning

There are principles of Talmudic hermeneutics which constitute an interesting method alternative, although related in some instances, to the syllogism. Three groups are listed: the 7 rules of Hillel, the 13 rules of R. Ishmael, and the 32 rules of R. Eliezer b. Jose Ha-Gelili (all come from the Jewish Encyclopedia 1906).

7 rules of Hillel

7 rules of Hillel

- Ḳal (ḳol) wa-ḥomer (קל וחומר): "Argumentum a minori ad majus" or "a majori ad minus"; corresponding to the scholastic proof a fortiori.

- Gezerah shawah (גזירה שוה): Argument from analogy. Biblical passages containing synonyms or homonyms are subject, however much they differ in other respects, to identical definitions and applications.

- Binyan ab mi-katub eḥad (בנין אב מכתוב אחד): Application of a provision found in one passage only to passages which are related to the first in content but do not contain the provision in question.

- Binyan ab mi-shene ketubim (בנין אב מכתוב אחד): The same as the preceding, except that the provision is generalized from two Biblical passages.

- Kelal u-Peraṭ and Peraṭ u-kelal (כלל ופרט ופרט וכלל): Definition of the general by the particular, and of the particular by the general.

- Ka-yoẓe bo mi-maḳom aḥer (כיוצא בו ממקום אחר): Similarity in content to another Scriptural passage.

- Dabar ha-lamed me-'inyano (דבר הלמד מעניינו): Interpretation deduced from the context.

- Ḳal wa-ḥomer: Identical with the first rule of Hillel.

- Gezerah shawah: Identical with the second rule of Hillel.

- Binyan ab: Rules deduced from a single passage of Scripture and rules deduced from two passages. This rule is a combination of the third and fourth rules of Hillel.

- Kelal u-Peraṭ: The general and the particular.

- u-Peraṭ u-kelal: The particular and the general.

- Kelal u-Peraṭ u-kelal: The general, the particular, and the general.

- The general which requires elucidation by the particular, and the particular which requires elucidation by the general.

- The particular implied in the general and excepted from it for pedagogic purposes elucidates the general as well as the particular.

- The particular implied in the general and excepted from it on account of the special regulation which corresponds in concept to the general, is thus isolated to decrease rather than to increase the rigidity of its application.

- The particular implied in the general and excepted from it on account of some other special regulation which does not correspond in concept to the general, is thus isolated either to decrease or to increase the rigidity of its application.

- The particular implied in the general and excepted from it on account of a new and reversed decision can be referred to the general only in case the passage under consideration makes an explicit reference to it.

- Deduction from the context.

- When two Biblical passages contradict each other the contradiction in question must be solved by reference to a third passage.

32 Rules of Eliezer b. Jose Ha-Gelili

- Ribbuy (extension): The particles 'et," "gam," and "af," which are superfluous, indicate that something which is not explicitly stated must be regarded as included in the passage under consideration, or that some teaching is implied thereby.

- Mi'uṭ (limitation): The particles "ak," "raḳ" and "min" indicate that something implied by the concept under consideration must be excluded in a specific case.

- Ribbuy aḥar ribbuy (extension after extension): When one extension follows another it indicates that more must be regarded as implied.

- Mi'uṭ aḥar mi'uṭ (limitation after limitation): A double limitation indicates that more is to be omitted.

- Ḳal wa-ḥomer meforash: "Argumentum a minori ad majus," or vice versa, and expressly so characterized in the text.

- 6. Ḳal wa-ḥomer satum: "Argumentum a minori ad majus," or vice versa, but only implied, not explicitly declared to be one in the text. This and the preceding rule are contained in the Rules of Hillel, No. 1.

- identical with Rule 2 of Hillel.

- identical with Rule 3 of Hillel

- Derek ḳeẓarah: Abbreviation is sometimes used in the text when the subject of discussion is self-explanatory.

- Dabar shehu shanuy (repeated expression): Repetition implies a special meaning.

- Siddur she-neḥlaḳ: Where in the text a clause or sentence not logically divisible is divided by the punctuation, the proper order and the division of the verses must be restored according to the logical connection.

- Anything introduced as a comparison to illustrate and explain something else, itself receives in this way a better explanation and elucidation.

- When the general is followed by the particular, the latter is specific to the former and merely defines it more exactly (comp. Rules of Hillel, No. 5).

- Something important is compared with something unimportant to elucidate it and render it more readily intelligible.

- Same as Rule 13 of R. Ishmael.

- Dabar meyuḥad bi-meḳomo: An expression which occurs in only one passage can be explained only by the context. This must have been the original meaning of the rule, although another explanation is given in the examples cited in the baraita.

- A point which is not clearly explained in the main passage may be better elucidated in another passage.

- A statement with regard to a part may imply the whole.

- A statement concerning one thing may hold good with regard to another as well.

- A statement concerning one thing may apply only to something else.

- If one object is compared to two other objects, the best part of both the latter forms the tertium quid of comparison.

- A passage may be supplemented and explained by a parallel passage.

- A passage serves to elucidate and supplement its parallel passage.

- When the specific implied in the general is especially excepted from the general, it serves to emphasize some property characterizing the specific.

- The specific implied in the general is frequently excepted from the general to elucidate some other specific property, and to develop some special teaching concerning it.

- Mashal (parable).

- Mi-ma'al: Interpretation through the preceding.

- Mi-neged: Interpretation through the opposite.

- Gemaṭria: Interpretation according to the numerical value of the letters.

- Noṭariḳon: Interpretation by dividing a word into two or more parts.

- Postposition of the precedent. Many phrases which follow must be regarded as properly preceding, and must be interpreted accordingly in exegesis.

- Many portions of the Bible refer to an earlier period than do the sections which precede them, and vice versa.

References:

Galen's Methods

A precursor of Ramus.

Durling, Method in Galen. DYNAMIS. Acta Hisp. Med. Sci. Hist. Illus., 15, 1995, 41-46.

See here

Durling, Method in Galen. DYNAMIS. Acta Hisp. Med. Sci. Hist. Illus., 15, 1995, 41-46.

See here

The Inductive grounding of Deductive Systems!

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy says that: "Reichenbach does not argue that induction is a sound method; his account is rather ...[a] vindication: that if any rule will lead to positing the correct probability, the inductive rule will do this, and it is, furthermore, the simplest rule that is successful in this sense."

The conclusions of inductions are not asserted, they are posited. “A posit is a statement with which we deal as true, though the truth value is unknown” (TOP, 373)

The flow of reasoning seems to be similar to Von Mises, and Mach, i.e. a Kantian, in that first observe nature empirically and from there derive mathematical concepts and axioms. In this way, even axioms are derived by induction and then, perhaps, generalizable by deduction.

Moreover, Moritz Schlick arrived to a similar conclusion, in that the

which is a very bold assertion to make! Induction is at the base of Deduction, where the latter is customarily considered to be superior to the former!

| J. Alberto Coffa circa 1973 from here |

The flow of reasoning seems to be similar to Von Mises, and Mach, i.e. a Kantian, in that first observe nature empirically and from there derive mathematical concepts and axioms. In this way, even axioms are derived by induction and then, perhaps, generalizable by deduction.

Moreover, Moritz Schlick arrived to a similar conclusion, in that the

"...the construction of a strict deductive science has only the significance of a game with symbols." GTK, 37 in Coffa, 176.Russell, against Poincare, held the same view:

Geometric indefinables [i.e. components of axioms] are first given to us in acquaintance [i.e. intuition]. Coffa, 132And also

Russell explained that the reasons we have for accepting a fomula as a truth of logic are "inductive". Coffa 124

which is a very bold assertion to make! Induction is at the base of Deduction, where the latter is customarily considered to be superior to the former!

Propositional attitudes

The proposition attitude, posited Russell, is our disposition towards the judgment's content. They include understanding, assuming, wondering, asserting, believing, desiring, imagining, feeling, affirming... See Coffa, 67.

Can the propositional attitudes be "aggregated"? See here

Can the propositional attitudes be "aggregated"? See here

| Diestrich and List (2010): Oxford Studies in Epistemology 3: 215-234, 2010 |

P. Ramus on Method - 2

Ramus proposes two types of Method

- Natural: which orders discourse in descending level of generality. Intended for Science. In this Ramus is not at odds with Quintilian who also advocated for the "natural" method. See here for the text.

- Prudential: which orders discourse suitably to teach the audience effectively. Intended for lay audiences.

These quotes are taken from McIlmaine's translation, who obliterates prudential method almost completely! (Howell, 183)

- Method is the intelligible order (dianoia) of various homogeneous axioms ranged one before the other according to the clarity of their nature, whereby the agreement of all is judged... As in the axiom one considers truth and falsity, and in the syllogism consequence or lack of consequence, so in method one sees to it that what is of itself clearer precedes (praecedeat), and what is more obscure follows, and that order and confusion in everything is judged.... Thus method proceeds (progreditur) without interruption from universals to singulars. By this one and only way one proceeds (proceditur) from antecedentes entirely and absolutely more known to the clarification of unknown consequents.

- Method is disposition (methodus est dispositio) by which, out of many homogeneous enunciations, each known by means of a judgment proper to itself [axiom] or by the judgment of syllogism, that enunciation is placed first which is first in the absolute order of knowledge [order of cognition], that next which is next, and so on. Thus there is a perpetual progression from universals to singulars.

Milton, (Logica, 473 Columbia Ed.) explains the relationship that there is between axiom, syllogism and method:

So as truth or falsity is seen in the axiom, in the syllogism consequence and inconsequence, so in method care is taken that what is clearer in itself should precede, what is more obscure should follow (dispositio); and in every way order and confusion are judged (judgment). Thus the first in absolute idea of the homogeneous axioms is disposed in the first place, the second in the second, the third in the third, and so on.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)