be your subject what it will, let it be merely simple and uniform.

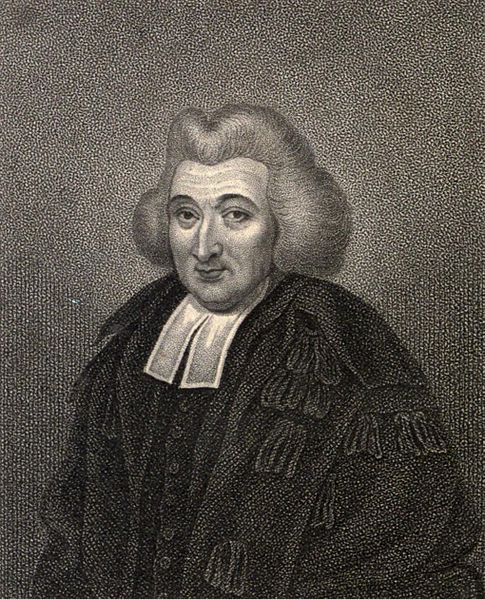

be your subject what it will, let it be merely simple and uniform.Very practical advice in the Works of the Rev. John Witherspoon, Lecture XI (on Eloquence), vol iii, p. 443.

...The next division of the oratorial art, is disposition or distribution. This is a matter of the utmost moment, and upon which instruction is both necessary and useful. By disposition as a part of the oratorial art, I mean order in general, in the whole of a discourse, or any kind of composition, be it what it will. As to the parts of which a single speech or oration consists, they will be afterwards considered. Before I proceed to explain or point out the way to attain good order, I would just mention a sew of its excellencies.

(1.) Good order in a discourse gives light, and makes it easily understood. If things are thrown together without method, each of them will be less understood, and their joint influence in leading to a conclusion will not be perceived. It is a noble expression of Horace, who calls it lucidus ordo, clear order. It is common to say, when we hear a confused discourse, "It had neither head nor tail, I could not understand what he would be at."

(2.) Order is necessary to force, as well as light. This indeed is a necessary consequence of the other, for we shall never be persuaded by what we do not understand. Very often the force of reasoning depends upon the united influence of several distinct propositions. If they are arranged in a just order, they will all have their effect, and support one another; if otherwise, it will be like a number of men attempting to raise a weight, and one pulling at one time, and another at another, which will do just nothing; but if all exert their power at once, it will be easily overcome.

(3.) Order is also useful for assisting memory. Order is necessary even in a discourse that is to have a transient effect; but if any thing is intended to produce a lasting conviction, and to have a daily influence, it is still more necessary. When things are disposed in a proper order, the same concatenation that is in the discourse, takes place in the memory, so that when one thing is remembered, it immediately brings to remembrance what has an easy and obvious connection with it. The association of ideas linked together by any tie is very remarkable in our constitution, and is supposed to take place from some impression made upon the brain. If we have seen two persons but once, and seen them both at the same time only, or at the same place only, the remembrance of the one can hardly be separated from the other. I may also illustrate the subject by another plain instance. Suppose I desire a person going to a city, to do three or four things for me that are wholly unconnected, as to deliver a letter to one person—to visit a friend of mine, and to bring me notice how he is—to buy a certain book for me, if he can find it—and to see whether any ship be to sail for Britain soon,—it is very possible he may remember some of them, and forget the others; but if I desire him to buy me a dozen of silver spoons, to carry them to an engraver to put my name upon them, and get a case to put them in, if he remembers one article, it is likely he will remember all of them. It is one of the best evidences that a discourse has been composed with distinctness and accuracy, if after you go away you can remember a good deal of it; but there are sometimes discourses which are pompous and declamatory, and which you hear with pleasure, and some sort of approbation, but if you attempt to recollect the truths advanced, or the arguments in support of them, there is not a trace of them to be found.

(4.) Order conduces also very much to beauty. Order is never omitted when men give the principles of beauty, and confusion is disgusted just on its own account, whatever the nature of the confused things may be. If you were to see a vast heap of fine furniture of different kinds lying in confusion, you could neither perceive half so distinctly what was there, nor could it at all have such an effect, as if every thing was disposed in a just order, and placed where it ought to stand; nay, a much smaller quantity, elegantly disposed, would exceed in grandeur of appearance a heap of the most costly things in nature.

(5.) Order is also necessary to brevity. A confused discourse is almost never short, and is always filled with repetitions. It is with thought in this respect, as with things visible, for, to return to the former similitude, a confused heap of goods of furniture fills much more room than when it is arranged and classed in its proper order, and every thing carried to its proper place.

Having shown the excellence of precision and method, let us next try to explain what it is; and that I may have some regard to method while I am speaking of the very subject, I shall take it in three lights:

1. There must be an attention to order in the disposition of the whole piece. Whatever the parts be in themselves, they have also a relation to one another, and to the whole body, (if I may speak so), that they are to compose. Every work, be it what it will, history, epic poem, dramatic poem, oration, epistle, or essay, is to be considered as a whole; and a clearness of judgment in point of method, will decide the place and proportion of this several parts of which they are composed. The loosest essay, or where form is least professed or studied, ought yet to have some shape as a whole; and we may say of it, that it begins abruptly or ends abruptly, or some of the parts are misplaced. There are often to be seen pieces in which good things are said, and well said, and have only this fault, that they are unseasonable and out of place. Horace says, in his Art of Poetry, what is equally applicable to every sort of composition, Denique sit quod vis simplex duntaxat et unum [be your subject what it will, let it be merely simple and uniform]; and shortly after, Infelix operis summa, quia ponere totum nesciet [he doesn't know how to accommodate the parts to the whole]. This judgment in planning the whole, will particularly enable a person to determine both as to the place and proportion of the particular parts, whether they be not only good in themselves, but fit to be introduced in such a work; and it will also (if I may speak so) give a color to the whole composition. The necessity of order in the whole structure of a piece, shows that the rule is good which is given by some, that an orator, before he begin his discourse, should concentrate the subject as it were, and reduce it to one single proposition, either expressed, or at least conceived in his mind. Every thing should grow out of this as its root, if it be in another principle to be explained; or refer to this as its end, if it be a point to be gained by persuasion. Having thus stated the point clearly to be handled, it will afford a sort of criterion whether any thing adduced is proper or improper. It will suggest the topics that are just and suitable, as well as enable us to reject whatever is in substance improper, or disproportionate to the design. Agreeably to this principle, I think, that not only the subject of a single discourse should be reducible to one proposition, but the general divisions or principal heads should not be many in number. A great number of general heads both burdens the memory, and breaks the unity of the subject, and carries the idea of several little discourses joined together, or to follow after one another.

2. Order is necessary in the subdivisions of a subject, or the way of stating and marshalling of the several portions of any general head. This is applicable to all kinds of composition, and all kinds of oratory, sermons, law-pleadings, speeches. There is always a division of the parts, as well as of the whole, either expressed formally and numerically, or supposed, though suppressed. And it is as much here as anywhere, that the confusion of inaccurate writers and speakers appears. It is always necessary to have some notion of the whole of a piece; and the larger divisions being more bulky, (so to speak), disposition in them is more easily perceived; but in the smaller, both their order and size is in danger of being less attended to. Observe, therefore, that to be accurate and just, the subdivisions of any composition, such I mean as are (for example) introduced in a numerical series, 1, 2, 3, &c . should have the following properties:

(1.) They should be clear and plain. Every thing indeed should be clear as far as he can make it, but precision and distinctness should especially appear in the subdivisions, just as the bounding lines of countries in a map. For this reason the first part of a subdivision should be like a short definition, and when it can be done, it is best expressed in a single term; for example, in giving the character of a man of learning, I may propose to speak of his genius, his erudition, his industry or application.

2. Order is necessary in the subdivisions of a subject, or the way of stating and marshalling of the several portions of any general head. This is applicable to all kinds of composition, and all kinds of oratory, sermons, law-pleadings, speeches. There is always a division of the parts, as well as of the whole, either expressed formally and numerically, or supposed, though suppressed. And it is as much here as anywhere, that the confusion of inaccurate writers and speakers appears. It is always necessary to have some notion of the whole of a piece; and the larger divisions being more bulky, (so to speak), disposition in them is more easily perceived; but in the smaller, both their order and size is in danger of being less attended to. Observe, therefore, that to be accurate and just, the subdivisions of any composition, such I mean as are (for example) introduced in a numerical series, 1, 2, 3, &c . should have the following properties:

(1.) They should be clear and plain. Every thing indeed should be clear as far as he can make it, but precision and distinctness should especially appear in the subdivisions, just as the bounding lines of countries in a map. For this reason the first part of a subdivision should be like a short definition, and when it can be done, it is best expressed in a single term; for example, in giving the character of a man of learning, I may propose to speak of his genius, his erudition, his industry or application.

(2.) They should be truly distinct; that is, everybody should perceive that they are really different from one another, not in phrase or word only, but in sentiment. If you praise a man first for his judgment, and then for his understanding, they are either altogether or so nearly the same, or so nearly allied, as not to require distinction. I have heard a minister, on John, xvii. 11. "Holy Father," &c . In showing how God keeps his people, says (1). He keeps their feet: "He shall keep thy feet from falling." (2.) He keeps their way: "Thou shalt keep him in all his ways." Now, it is plain, that these are not two different things, but two metaphors for the same thing. This indeed was faulty also in another respect; for a metaphor ought not to make a division at all.

(3.) Subdivisions should be necessary; that is to say, taking the word in the loose and popular sense, the subject should seem to demand them. To multiply divisions, even where they may be made really distinct, is tedious, and disgustful, unless where they are of use and importance to our clearly comprehending the meaning, or feeling the force of what is said. If a person, in the map of a country, should give a different color to three miles, though the equality of the proportion would make the division clear enough, yet it would appear disgustingly superfluous. In writing the history of an eminent person's life, to divide it into spaces of ten years, perhaps, would make the view of the whole more exact; but to divide it into single years or months, would be finical and disagreeable. The increase of divisions leads almost unavoidably into tediousness.

(4.) Subdivisions should be coordinate; that is to say, those that go on in a series, 1, 2, 3, &c. should be as near as possible similar, or of the same kind. This rule is transgressed, when either the things mentioned are wholly different in kind, or when they include one another. This will be well perceived, if we consider how a man would describe a sensible subject, a county for example; New-Jersey contains, 1. Middlesex. 2. Somerset county. 3. The townships of Princeton. 4. Morris county. So, if one, in describing the character of a real Christian, should say, faith, holiness, charity, justice, temperance, patience, this would not do, because holiness includes justice, &c. When, therefore, it seems necessary to mention different particulars that cannot be made coordinate, they should be made subordinate.

(5.) Subdivisions should be complete, and exhaust the subject. This, indeed, is common to all divisions, but is of most importance here, where it is most neglected. It may be said, perhaps, How can we propose to exhaust any subject? By making the divisions suitable, particularly in point of comprehension, to the nature of the subject; as an example, and to make use of the image before introduced, of giving an account of a country, I may say, the province of New Jersey consists of two parts, East and West Jersey. If I say it consists of the counties of Somerset, &c. I must continue till I have enumerated all the counties, otherwise the division is not complete. In the same manner, in public speaking, or any other composition, whatever division is made, it is not legitimate, if it does not include or exhaust the whole subject; which may be done, let it be ever so great. For example: True religion may be divided various ways, so as to include the whole; I may say, that it consists of our duty to God, our neighbor, and ourselves; or, I may make but two, our duty to God and man, and divide the last into two subordinate heads, our neighbor, and ourselves ; or, I may say, it consists of faith and practice; or, that it consists of two parts, a right frame and temper of mind, and a good life and conversation.

(6.) Lastly, the subdivisions of any subject should be connected, or should be taken in a series or order, if they will possibly admit of it. In some moral and intellectual subjects, it may not be easy to find any series or natural order, as in an enumeration of virtues, justice, temperance, and fortitude. Patience, perhaps, might as well be enumerated in any other order; yet there is often an order that will appear natural, and the inversion of it unnatural; as we may say, injuries are done many ways to a man's person, character, and possessions. Love to others includes the relation of family, kindred, citizens, countrymen, fellow-creatures.

3. In the last place, there is also an order be observed in the sentiments, which makes the illustration or amplification of the divisions of discourse. This order is never expressed by numerical division, yet it is of great importance, and beauty and force will be particularly felt. It is if I may speak so, of a finer and more delicate nature than any of the others, more various, and harder to explain. I once have said, that all reasoning is of the nature of a syllogism, which lays down principles, makes comparisons, and draws the conclusion. But we must particularly guard against letting the uniformity and formality of a syllogism appear. In general, whatever establishes any connection, so that it makes the sentiments give rise to one another, is the occasion of order; sometimes necessity and utility point out the order as a good measure: As in telling a story, grave or humorous, you must begin by describing the persons concerned, mentioning just as many circumstances of their character and situation as are necessary to make us understand the facts to be afterwards related. Sometimes the sensible ideas of time and place suggest an order, not only in historical narrations, and in law-pleadings, which relate to facts, but in drawing of characters, describing the progress and effects of virtue and vice, and even in other subjects, where the connection between those ideas and the thing spoken of is not very strong. Sometimes, and indeed generally, there is an order which proceeds from things plain, to things obscure. The beginning of a paragraph should be like the sharp point of a wedge, which gains admittance to the bulky part behind. It first affirms what every body feels, or must confess, and proceeds to what follows as a necessary consequence. In fine, there is an order in persuasion to a particular choice, which may be taken two ways with equal advantage, proceeding from the weaker to the stronger, or from the stronger to the weaker: As in recommending a pious and virtuous life, we may first say it is amiable, honorable, pleasant, profitable, even in the present life; and, to crown all, makes death itself a friend, and leads to a glorious immortality: or, we may begin the other way, and say it is the one thing needful, that eternity is the great and decisive argument that should determine our choice, though every thing else were in favor of vice; and then add, that even in the present life, it is a great mistake to think that bad men are gainers, &c. This is called sometimes the ascending and descending climax. Each of them has its beauty and use. It must be left to the orator's judgment to determine which of the two is either fittest for the present purpose, or which he finds himself at that time able to execute to the greatest advantage.

REFERENCE

HERE

REFERENCE

HERE