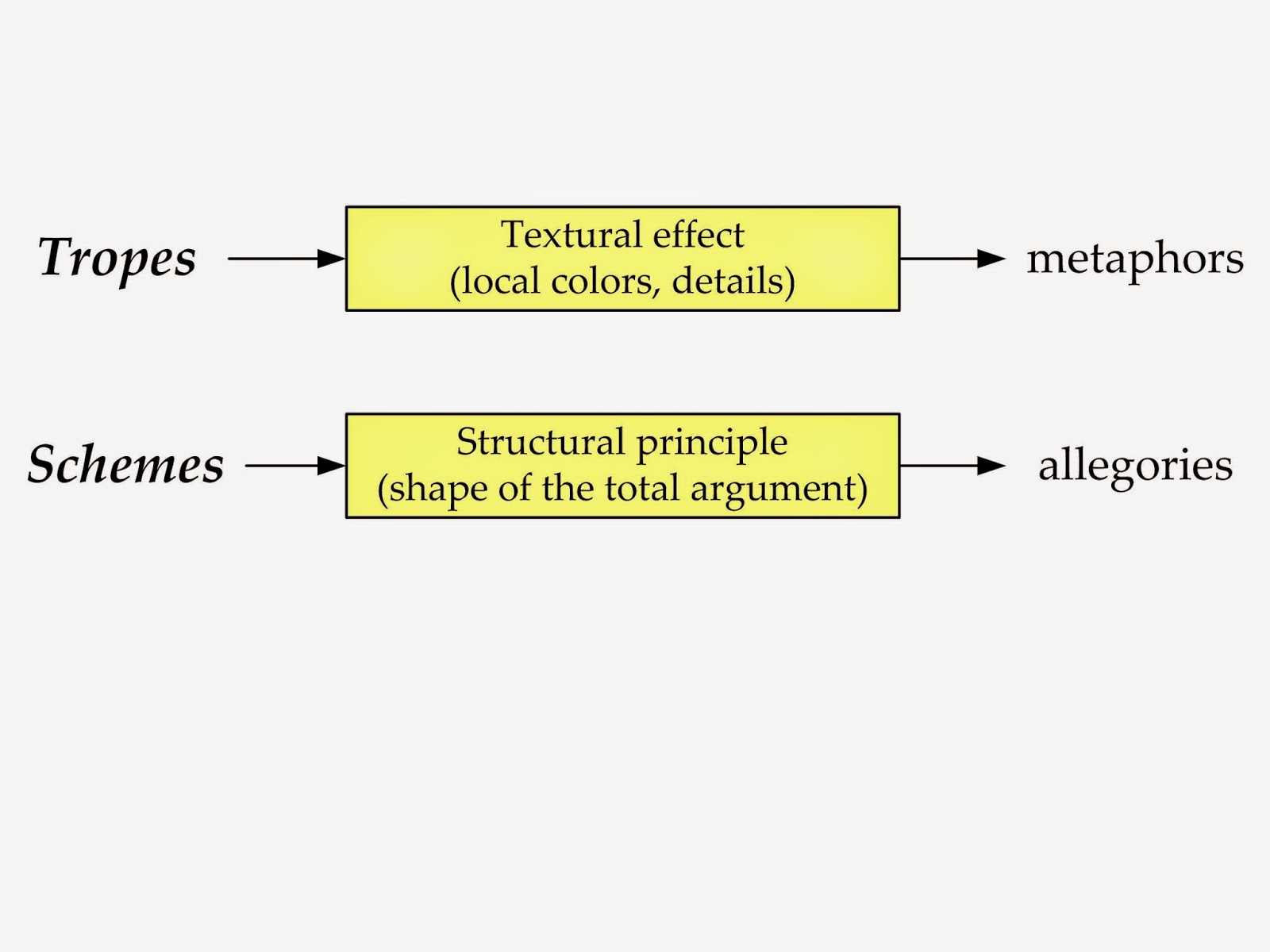

The author of the Rhetoric entry in the Enc. Brit. (5th, Vol. 26, p. 804) offers a useful functional distinction of tropes and schema:

Ancient rhetoricians made a functional distinction between trope (like metaphor, a textural effect) and scheme (like allegory, a structural principle). To the former category belong such figures as metaphor, simile (a comparison announced by "like" or "as"), personification (attributing human qualities to a nonhuman being or object), irony (a discrepancy between a speaker's literal statement and his attitude or intent), hyperbole (overstatement or exaggeration) or understatement, and metonymy (substituting one word for another which it suggests or to which it is in some way related--as part to whole, sometimes known as synecdoche).

To the latter category (scheme) belonged such figures as allegory, parallelism (constructing sentences or phrases that resemble one another syntactically), antithesis (combining opposites into one statement--"To be or not to be, that is the question"), congeries (an accumulation of statements or phrases that say essentially the same thing), apostrophe (a turning from one's immediate audience to address another, who may be present only in the imagination), enthymeme (a loosely syllogistic form of reasoning in which the speaker assumes that any missing premises will be supplied by the audience), interrogatio (the "rhetorical" question, which is posed for argumentative effect and requires no answer), and gradatio (a progressive advance from one statement to another until a climax is achieved).

No comments:

Post a Comment